When creating a visual work, including animation, a plan is developed and its content is concretized into a script (scenario). The script includes the location, time, scene, characters’ actions, and lines of the story. The image of that scene is further concretized, and the completed anticipated figure is a storyboard (Director Hayao Miyazaki often draws storyboards directly instead of scripting).

The term “storyboard” comes from the English word “continuity,” indicating continuousness. Things written in characters or text from scripts are divided by lines into what are called text storyboards, and things drawn in pictures are called storyboards. Both serve the same purpose, accurately conveying the director’s image to the staff. Text storyboards are often used in TV and stage productions, and in the case of animation, the entire original picture and background picture are drawn based on the storyboard. It plays a vital role because various tasks proceed simultaneously in different parts.

Even in live-action movies, storyboards are commonly used for complex scenes such as fight scenes or car chases, scenes involving special effects (SFX) or CG, or scenes that do not exist in reality.

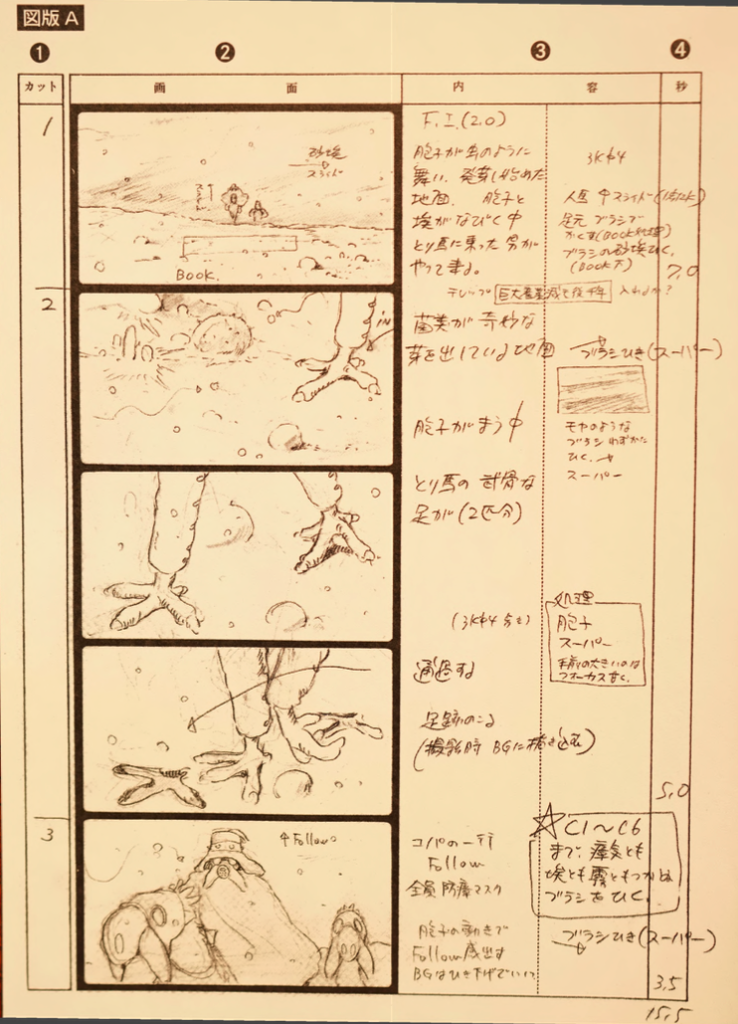

Storyboards are drawn on the studio’s exclusive paper (the storyboard original size for “Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind” is 364 x 257 mm), with five frames drawn vertically on each page, and actions, lines, effects, and intentions for direction are written in the margins.

In Japan, storyboarding is usually the director’s job, but there are cases where the director himself draws, like Director Hayao Miyazaki, and there are cases where the director draws rough storyboards, and a partner draws them in more detail, like Director Isao Takahata. Either way, layout design is done within the storyboard, and the picture is drawn precisely. The content of the script often changes significantly at the storyboard stage, and drawing the storyboard is the most important task in animation production.

Like a building blueprint, storyboards have parts that can be understood even by non-professionals and parts that can only be understood by professionals. Drawing A is the storyboard of the opening scene of “Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind”, and I will explain how to view the storyboard using this as an example.

The far left 1 is the cut number. It shows the order of cuts in the work, with continuous numbers from the beginning or by part. For example, the bottom picture is called cut 3.

2 is a picture that specifically depicts the contents of the scene drawn in the script. Like cut 2, there are cases where the movement of one cut is divided into several frames. In live-action works, the shooting and editing work is specified in advance in the storyboard.

3 is an explanation of the picture drawn on the screen written in the left space. Mainly explanations of camera work for each cut, character movements, supplemental psychological states, etc. are written. In the right space, the lines for that cut are written. Instructions for sound effects and music, as well as direction and shooting methods, are also written. Specialized terms such as superimposition (スーパー) and follow (フォロー) are used.

4 indicates the duration of each cut in seconds. For example, “7.0” in cut 1 refers to 7.0 seconds. The number written at the bottom outside of the frame is the total duration of all cuts on that page. As it is written “15.5”, this indicates that the total time from cut 1 to cut 3 is 15.5 seconds. The sum of the duration of all the storyboard cuts will be the screening time. In the case of a TV series, since the runtime is predetermined, it is necessary to fit the entire show from the first to the last cut within that time frame.

The professional terms in 3 and the time in 4 may be difficult to understand for non-professionals, but by reading the images in 2 and the content in 3, you can deepen your understanding of each scene and enjoy the work more.

While you can enjoy a work by watching it from beginning to end, it’s not possible to gather detailed information about every cut, every scene. In live-action works, there are instances where the camera unintentionally captures unwanted objects or scenery, but in animation, it can be said that everything drawn on the screen carries some kind of meaning or information.

Illustration A is the first scene of the movie, and since there are no lines, the information comes only from what is visually perceived. Later, you’ll understand that Yupa, riding a Toriuma, is walking down a path filled with spores. But if you read the storyboard, you’ll find out that it was originally planned to insert the caption “a thousand years after the collapse of the giant industry” with a telop, and you’ll also realize that the thing under the feet of the Toriuma is a fungus that is sprouting.

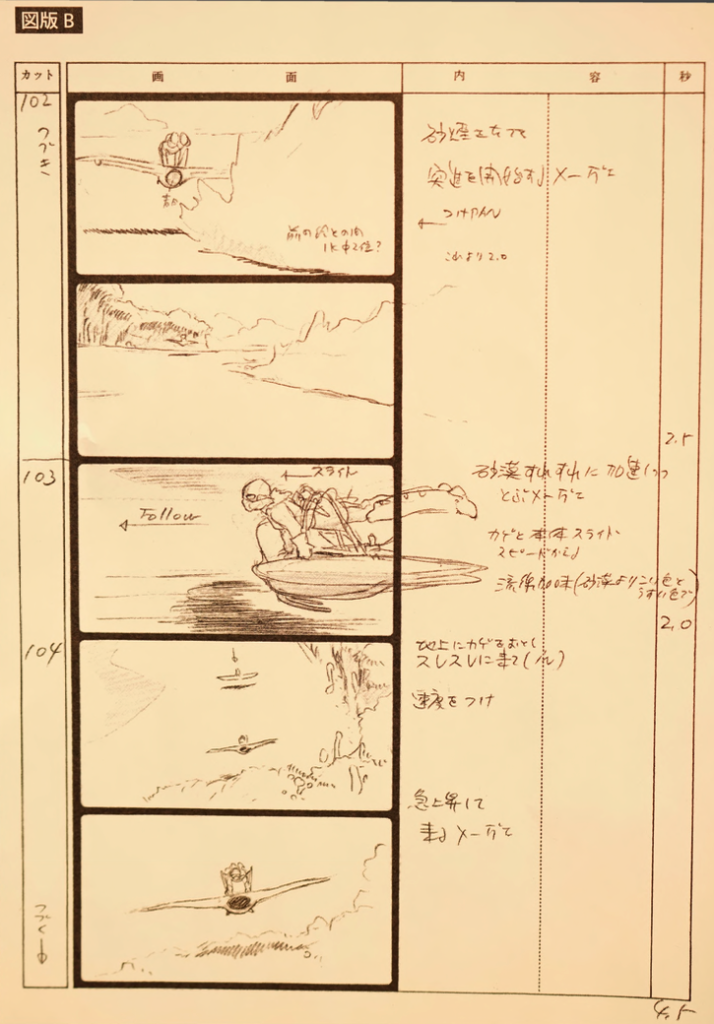

We can ordinarily observe vehicles like cars and bicycles or animals like dogs and cats, so we understand their form and how they move. However, for imaginary vehicles or animals, only the director or specialized staff who conceived them can understand. When you watch the work, you understand the form and movement of the Mēve, the Ohmu, or the Giant Warrior, because they are shown in specific illustrations. In drawing B , the flight of the Mēve is carefully instructed. You can understand that the smooth movement of the Mēve is born from here.

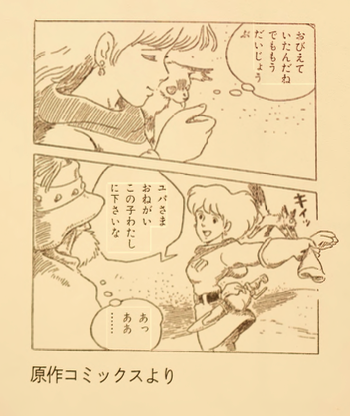

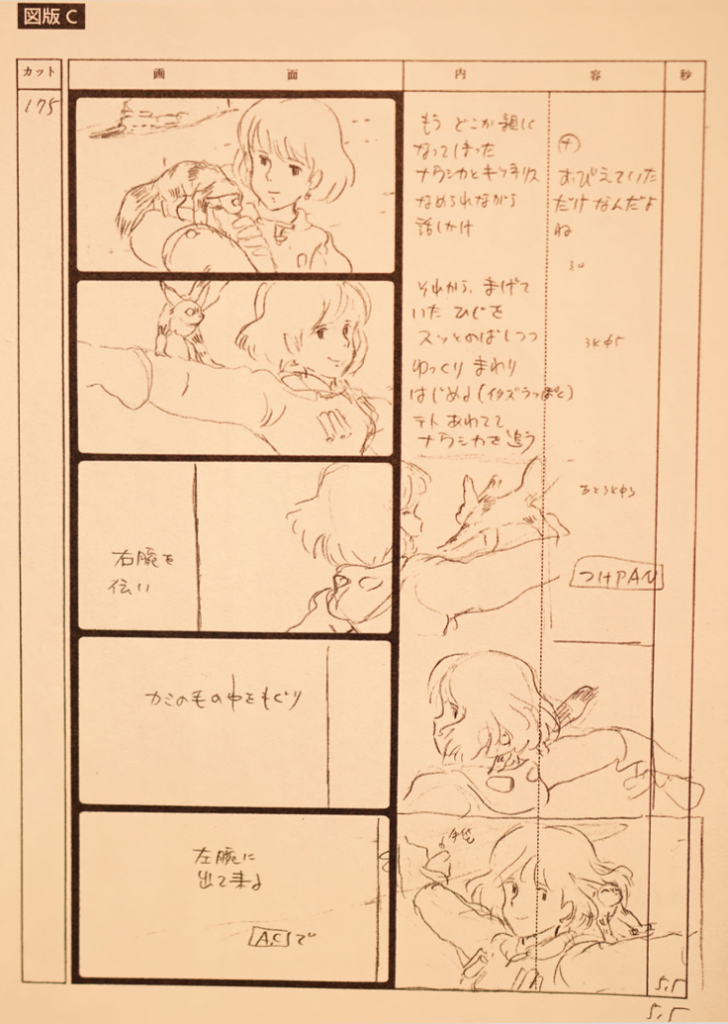

“Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind” is a film born from the comics drawn by the director himself. There are scenes drawn specifically for the film, like the opening, as well as cuts (frames) that are the same as in the comics. Illustration 3 (page 185) divides a picture that was drawn in two frames in the comic into several frames, and gives specific instructions for the movements. From the storyboard, the director’s thoughts that were put into this cut come through.

From the Manga.

From Storyboard or Ekonte (絵コンテ)

These are just a few examples, but when you read the storyboard, you can see the finished anticipated figure that the director first envisioned. When the work begins to move concretely, new images that were not in the storyboard may be added, or conversely, some may be cut.

The finished work is the final form of what was created over a long period of time, but by reading the storyboard, you can understand the work more deeply and enjoy it on a larger scale.