By Naoki Inagaki

Hayao Miyazaki’s thoughts on Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Pilots do not speak much.

Hayao Miyazaki also does not speak much, but he has said the following about Antoine de Saint-Exupéry:

“I was most influenced by Saint-Exupéry, after all.”

On May 9, 1998, the Japanese television series “World, My Heart’s Journey” aired an episode titled “Dream of the Sky from Saint-Exupéry: From Southern France to Sahara” featuring Hayao Miyazaki. In Miyazaki’s book “Flying Boat Era: Original Work for the Movie ‘Porco Rosso,'” there’s a brief mention of this episode, noting it as “a program retracing the footsteps of Saint-Exupéry, the author who greatly influenced Director Miyazaki.” This remark can be considered an “official” recognition of Saint-Exupéry’s impact on Miyazaki.

Miyazaki, known as a fan of Saint-Exupéry even before the recording of this program, was asked to visit the places related to Saint-Exupéry by chartering an old biplane Antonov AN-2. That was the program’s project. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (1900-1944), the author of “The Little Prince” (1943), was both a writer and a pilot, initially a pilot for the airmail transport company Latécoère. The program begins with a flight from Paris to Toulouse, the base of the company, in southern France. From there, it follows the same route as the old airmail, crossing the Strait of Gibraltar from Spain to North Africa. The plan was to cross the Atlas Mountains from Marrakesh, Morocco, and enter the Sahara Desert. The program was richly recorded with the thoughts and interview footage of Miyazaki picked up by the microphone at his mouth, and it was a valuable record.

Miyazaki’s flight destination was Cap Juby in the western Sahara Desert. It was the site of an airfield where Saint-Exupéry had spent a year and a half, from October 1927 to March 1929, alone as the airfield manager and employee. In this desert, while tormented by loneliness, he completed his first novel, “Southern Mail” (1929), while fulfilling his responsibilities. In a year and a half in the desert, Saint-Exupéry, who had not been able to rise at all, was reborn as a confident pilot and writer. Overlooking the site of the Cap Juby airfield from above, Miyazaki was visibly moved, took off his glasses, and held his eyes with a handkerchief. Then, after that, he quietly, spontaneously, and probably honestly, spoke his mind.

In the program, Miyazaki shared his fondness for “Terre des Hommes” (Wind, Sand and Stars) from his student years. In his reading guide for young readers, “Door to Books,” he not only insists that everyone should read “The Little Prince” at least once but also passionately recommends “Terre des Hommes,” urging readers to delve into it as they mature.

“The Sky Itself” and the Literary Expression of Aviators

During an interview for the TV program “World, My Heart’s Journey”, Miyazaki expressed high regard for Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s “Night Flight”. He admired its vivid and precise depictions of weather and airplanes, capturing “the very essence of the sky.” Additionally, he valued its portrayal of relationships between those on the ground and those flying, especially appreciating its legacy of “enshrining pilots in literature”. These sentiments are echoed in Miyazaki’s piece “Sacrifices of the Sky”.

One can easily recognize the first point by remembering the many flight sequences in “Porco Rosso”. Consider the chase where Porco Rosso, in his treasured Savoia S-21 known as Fiolgore, pursues the Dabohaze seaplane of the pirate gang over the Piccolo Islands. Or when Porco, with Fio aboard his newly repaired aircraft, soars from Milan’s skies to the Adriatic Sea. Recall the moment Porco shares his wartime tales with Fio, gazing at the ascending dead seaplanes in the sky, reminiscent of the Milky Way, after a fierce dogfight with Austrian military aircraft. Then there’s the aerial duel between Porco and Donald Curtis, piloting a Curtis R3C-0, where stakes are Fio and the Fiolgore’s repair costs. And who could forget the majestic journey of the Fiolgore through the Adriatic sky’s layers of clouds and sunbeams, heading to Milan for refurbishment? The sheer beauty of this final scene is undeniably captivating.

The second point can be interpreted as such (this is my perspective, at least). Aviators, through sheer physical strength and more importantly, by pushing their mental boundaries, managed the challenging task of airmail delivery, showcasing the nobility of the human spirit. In creating a character like Porco Rosso, Miyazaki channels the essence of aviators as portrayed by Saint-Exupéry, including those who tragically lost their young lives. In doing so, Miyazaki not only draws inspiration from Saint-Exupéry’s homage to pilots in literature but also reflects on his own constraints. Through this lens, he conveys their profound “purpose in life” to audiences. Could this be an underlying theme in Miyazaki’s “Porco Rosso”?

The Mystery of the End Roll Illustrations

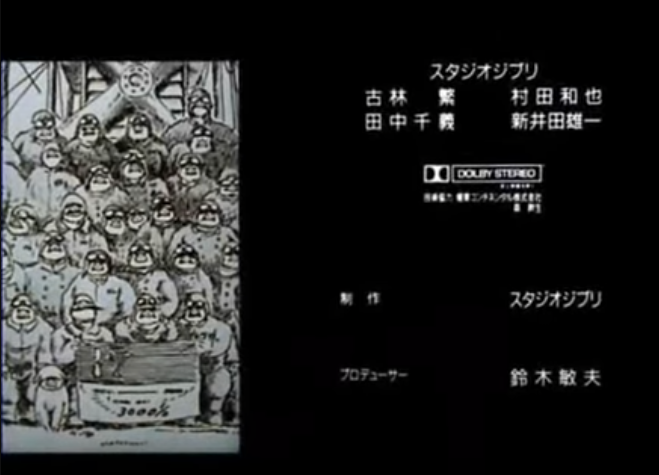

While the ending theme “Once in a While, Talk of the Old Days” by Tokiko Kato plays, one might wonder about the surprisingly modest end roll, where sepia-toned, lightly colored illustrations appear on the left third of the screen, changing at regular intervals.

These 22 images serve as snapshot glimpses into the lives of ordinary, uncelebrated individuals from a past era, specifically the time following the 1929 Great Depression, described as “an old tale.” Intriguingly, this time also marks the rise of Saint-Exupéry as both an airmail pilot and a writer. All these 22 illustrations can be found in the book “Once in a While, Talk of the Old Days,” jointly penned by Hayao Miyazaki and Tokiko Kato. Editorial notes mention they were “expressly illustrated by Mr. Hayao Miyazaki for the ‘Porco Rosso’ movie ending.” Every image in the book is accompanied by a caption, deemed its title, absent in the movie’s end credits.

Of these illustrations, several (perhaps in the dozens, based on one’s interpretation) appear to have connections to Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s works. A few (three, specifically) don’t just relate but carry titles of Saint-Exupéry’s books or chapter headings as their captions. While not all images might align perfectly with the song’s lyrics, potential correlations exist. Illustrations titled after Saint-Exupéry’s “Southern Mail” (1929) and subsequent “Night Flight” (1931) unmistakably showcase the Breguet 14 biplanes utilized in Latécoère’s initial airmail ventures (the distinct, almost box-like engine and radiator’s design are tell-tale signs). The “Southern Mail” image appears alongside lyrics that echo sentiments from the previous song: “Carried by the searing breezes of a tumultuous time, I embraced the moment fully,” followed by an affirming “That’s right.” This affirmation could also be seen as an acknowledgment of the song’s initial lines: “Shall we reminisce about the past sometimes?” As the first verse concludes, the “Night Flight” image emerges during the interlude stemming from “That’s right.” If one sees this as an intentional synchronization between visuals and lyrics, it paints a vivid picture: the lives of individuals in Saint-Exupéry’s narratives who “embraced the moment, carried by the searing breezes of a tumultuous era,” and the recognition of recounting such tales as “old stories,” affirmed by “That’s right.”

The Pilots Give “Meaning to Life”

The second chapter of “Wind, Sand and Stars” (1939) carries a French title often translated as “friends” or “colleagues”. However, in the version commented upon by Miyazaki, it’s rendered as “comrades.” An illustration with the title “comrades” is found amongst the movie’s end credits. It shows an artwork transformed from a commemorative photograph featuring roughly thirty pilots dressed in flight suits and goggles, arranged in five rows before a biplane. This aircraft is evocative of the Breguet 14 used in airmail journeys, albeit with a different propeller count. This image aligns with the third verse’s starting line, “Take a look at this remaining photo”, followed by lyrics from the previous picture: “I can’t admit to anyone that everything from that day feels void”, and “Even now, I’m still chasing my dreams.”

In “Wind, Sand and Stars,” the chapter titled “Comrades” gives voice to the pilots’ unyielding, transcendent spirit through Saint-Exupéry’s lens. It captures the brave undertakings of airmail pilots like Jean Mermoz and Henri Guillaumet and their irreplaceable bond. Through the juxtaposition of imagery and lyrics, their lives may be interpreted not as “void” but as perpetually “unrealized dreams.” The film’s theme song, “When the Cherry Berries Ripen,” performed by Gina (voiced by Tokiko Kato), is a nostalgic piece reflecting on the Paris Commune (viewed as the inaugural “socialist government” established and sustained by workers in 1871 for around two months). It has been sung across generations with the sentiment, “everything feels void, a feeling I can’t share with anyone.”

Within the 22 illustrations, every man is depicted with the same pig visage as Porco Rosso. The “Comrades” image, showcasing around thirty pig-faced aviators, stands out remarkably. Each of these aviators embodies the “pig” essence, all converging into the pilot Porco Rosso (Red Pig). Captain Marco Pagot, a retired air force pilot, transforms himself into “Red Pig” Porco Rosso as a self-imposed curse, driven by his disgust with the cruelty of the state, society, and, at its core, humanity after witnessing the horrors of war. Miyazaki contends that humans’ innate attraction to airplanes stems from an undying “yearning for power and speed” that aligns paper-thin with human savagery.

Youth, captivated by airplanes, piloted fighters during World War I and later took on airmail flights. Unfortunately, many met untimely ends. An introductory note in “The Land of Humans” accentuates that aviation’s legacy is littered with youthful casualties. Perhaps the same deep-seated “indomitable human discontent” drives Miyazaki’s penchant for “adventure dramas,” leading him to animate them.

Fully cognizant of such sentiments, Miyazaki often shows restraint in his works when illustrating combat sequences, being careful to avoid fatalities. “Porco Rosso,” given its theme, displays heightened discretion. While pursuing the Mamma Aiuto Gang’s aircraft, Porco aims solely at the engine and a single vertical tail, steering clear of human targets. Even during the climactic aerial duel with Curtis, Porco’s strategy is to “fire a few shots at the engine once the opponent stabilizes,” deliberately avoiding firing. The ultimate verdict is settled not in the skies but with a boxing match on the sea’s surface.

Taking this into account, it’s essential to revisit the influence of British author Roald Dahl on the narrative. True, the brief air skirmish between Porco and the Austrian military fighter plane, lasting a mere ten seconds, and the subsequent vast procession of airships he observes after breaking through the clouds, seem directly inspired by Dahl’s short story “They Shall Not Grow Old” from his “Tales of the Unexpected” collection.

However, there’s a stark contrast between the ethos of Dahl and that of Saint-Exupéry. While Dahl’s collection captures the wartime experiences of a British Air Force fighter squadron during World War II—highlighting aerial combats, shoot-downs, and essentially tales centered around fatalities—Saint-Exupéry’s narratives predominantly revolve around the non-combative realm of airmail delivery. His later piece, “Flight to Arras,” even though grounded in his personal experiences from World War II, depicts his tenure in a reconnaissance flying unit. Confrontations with enemy aircraft typically resulted in evasive maneuvers or getting shot down, rather than engaging in combat. It’s poignant to note that Saint-Exupéry’s own demise came as he was gunned down during a return journey from a reconnaissance mission.

Influenced by the raw, unbridled “urge for power and velocity,” Saint-Exupéry crafted his tales celebrating aviators who risked it all for postal deliveries, grounded in the belief that “we must imbue life with meaning” (an editorial headline in “Paris-Soir” dated October 4, 1938). “Porco Rosso” seems to resonate deeply with this sentiment. Miyazaki, fully conscious of his unique lens and constraints as an animator, celebrated the legacy of yesteryear’s aviators who refused to concede to the notion of futility. It’s hard not to view this film as a culmination of such inspiration.

Inagaki Naoki. Born in Aichi Prefecture in 1951. Professor at Kyoto University Graduate School. Doctoral course completed at the University of Tokyo Graduate School. Doctor of Literature from the University of Paris. Japan Translation Culture Award recipient. Specializes in French literature, Japanese-French comparative literature and culture, such as Victor Hugo, Saint-Exupéry, etc. His translation of “The Little Prince” is popular among many readers as a “classic translation”. Recent works include “The Story of ‘The Little Prince'”, “French Spiritual Science Considered”, and “Re-reading ‘Les Misérables'”.