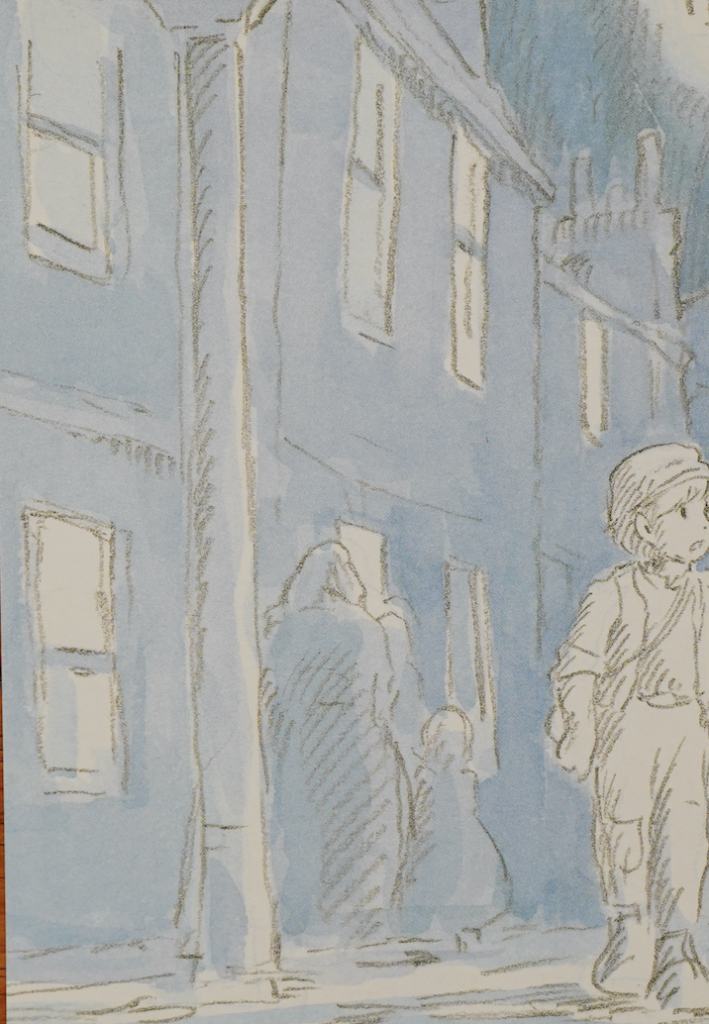

The first north wind of the year, which began blowing in the evening, was gusting down from the hill of Lord Slagg’s residence. The tin plates of the scrap yard were making a strange sound.

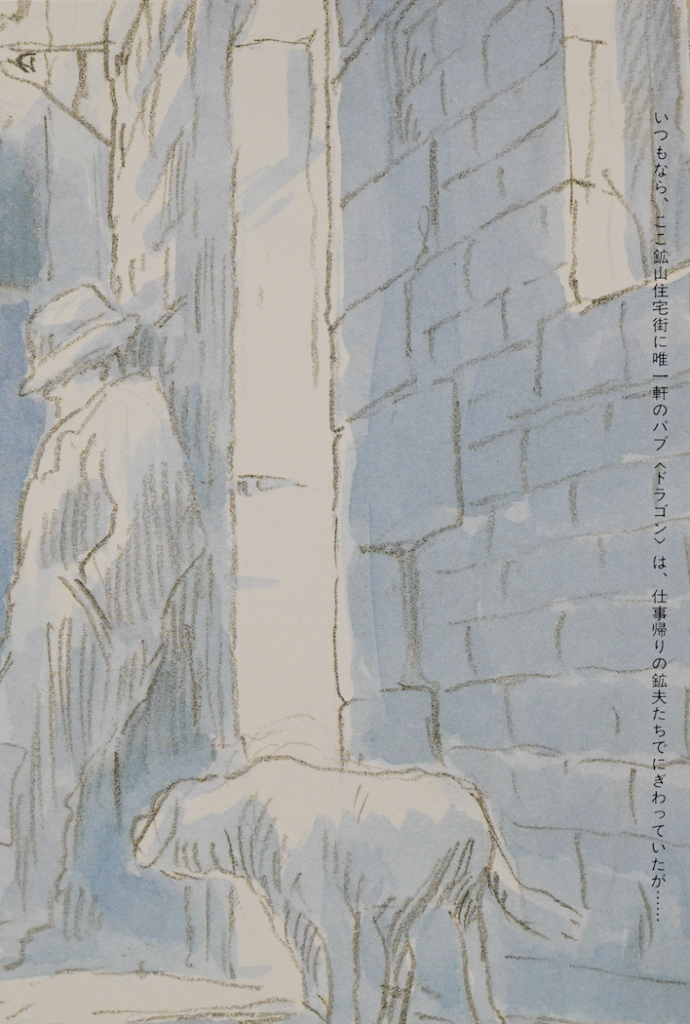

Usually, the only pub in the mining residential area, “Dragon”, is bustling with miners returning from work. Perhaps more keen on winter preparations, they went home early that night.

Still, some groups of men were holding glasses and raising their voices.

Prominently among them was the baritone voice of Pazu’s boss.

“That’s right, don’t make me laugh. We too want to dig more. But nothing comes out, right? And they accuse us of slacking off, having some weird guy keep an eye on us.”

It seems that they are talking about the same old issues, as the miners sitting with him were getting visibly fed up.

“Shut down this mine!”

“Duffy, it’s as if it’s already shut down.”

“What? Are you planning to close it?”

The miners, looking resigned, exchanged glances and quietly stood up, leaving grumbling Duffy behind.

Taking their place was Pazu.

“Pazu, take care of Duffy.”

“What happened? I heard loud voices.”

“Well, just like the machinery in the mines, sometimes people malfunction too. See ya.”

As the miner left, Pazu sat down in front of his boss.

“Boss, let’s go home.”

“Pazu, have you finished cleaning up?”

Having seen his friends leave, the boss’s voice had lost some of its vigor.

“Yeah, all done.”

“Want something to drink?”

“No thanks, I had a drink earlier.”

Knowing that the boss’s life was not easy, Pazu hesitated, even if it was just a glass of juice.

The boss did not press any further. He wasn’t in the mood to force Pazu to drink beer and laugh like other nights.

“Pazu, have you ever thought about growing wings and flying away somewhere?”

The boss took a sip from his glass.

“When I watch pigeons, I feel like I want to fly with them.”

“Pigeons? How are yours doing?”

“Yeah, they had babies. Now there are seven. They can fly with their parents now.”

“Parents…”

The boss gazed at Pazu for a moment and then stood up, saying, “Let’s go.”

Outside, it was already dark, and the cold wind was still blowing.

On his way back to his hut on the hill, after dropping off the boss, Pazu wondered why the boss had become so aggressive lately.

It all started about six months ago when rumors spread that the mine owner said,

“We will decisively close down unprofitable areas.”

At that time, the bosses took their lunches and went to the distant town for a protest.

“Do they expect us to abandon the mountain we’ve worked on since our ancestors’ time? Some have lost parents and siblings. Haven’t they profited because of us?”

It was said that the boss’s energy at that time was extraordinary.

They seemed to have settled on “let’s wait and see,” but since then, no significant veins of ore were found. The situation remained unchanged.

Speaking of Pazu’s status as a “mechanic apprentice,” it’s essentially a low-level laborer. The mine owners, to avoid paying a proper wage to adults, took advantage of boys like Pazu. The fact that he was young didn’t grant him any leniency. He had to work as hard as an adult to prove his “worth.”

Pazu understood this. He also knew that there were many other boys who could replace him. On cold days like this, even without seeing the boss’s aggravated state, Pazu felt an unsettling restlessness.

Walking faster than usual, Pazu soon arrived at his hut on the hill. Even after entering his room, his body still felt warm.

“I don’t need the stove tonight.”

Wood was becoming scarce. He didn’t want to use it much.

Pazu took a lamp and opened the lid of the pot left on the stove. There were leftovers from yesterday’s potato stew.

He ate directly from the pot with a spoon and finished it quicker than he thought.

That was his dinner.

Pazu sighed, standing, and closed his eyes.

The fatigue from the morning suddenly hit him, and he felt a sense of emptiness, as if being engulfed by darkness.

“Should I just sleep now…”

For a moment, he thought so, but habitually, his feet headed towards the stairs leading to the basement.

Pazu’s hut was built leaning against the remnants of an old blast furnace, so the “basement” refers to the inside of the furnace dome.

Descending into the cold, brick-lined basement, Pazu sat in one corner.

What the lamp illuminated was an ornithopter, a bird-shaped aircraft he’d been building for a long time.

“Will it really fly…?”

He often doubted himself, especially when faced with complex parts.

“No, I will make it fly for sure.”

Supported by this unwavering thought, though still a mere skeleton, it was slowly taking shape.

He was currently working on the wings.

“Quite tired tonight, but I’ll try to carve at least one rib.”

Building the aircraft was on his own time.

Pazu turned off the lamp and lit a tray of waste oil he got from the factory.

The next morning, Pazu was awakened by the sound of machinery from the early-rise factory.

“Damn it.”

Usually, he woke up to the first siren that sounded from the edge of the valley. It was only a slight difference, but it was significant for Pazu in the morning.

In a rush, he pulled on his pants, hurried down the steep stairs, washed his face with the rainwater stored in the basement’s jar, rinsed his mouth, and gulped it down.

The tools from last night’s airplane-making were still out, but he didn’t have time.

Returning to the room above, he quickly changed into his work clothes, stuffed two slices of bread into his pocket, slung his tool bag over his shoulder, and raced up the stairs to the roof.

Outside, it was drizzling.

The pigeons, kept in a section above the furnace, puffed up their chests and cooed happily at the sight of Pazu.

“No trumpet today.”

Usually, in the morning after releasing the pigeons into the sky, he’d play his trumpet while watching their shining white figures soar over the valley.

He opened the pigeon coop door and swiftly descended the uneven bricks of the furnace, leaping onto the road below.

The bottom of the valley was still dark. Smoke rose from the miners’ homes below, but hardly anyone was around.

Pazu ran while stuffing bread into his mouth. The cold morning rain stung his skin.

The reason Pazu had to get to the mine entrance earlier than the regular miners and technicians was to prepare everything so they could start working as soon as they arrived.

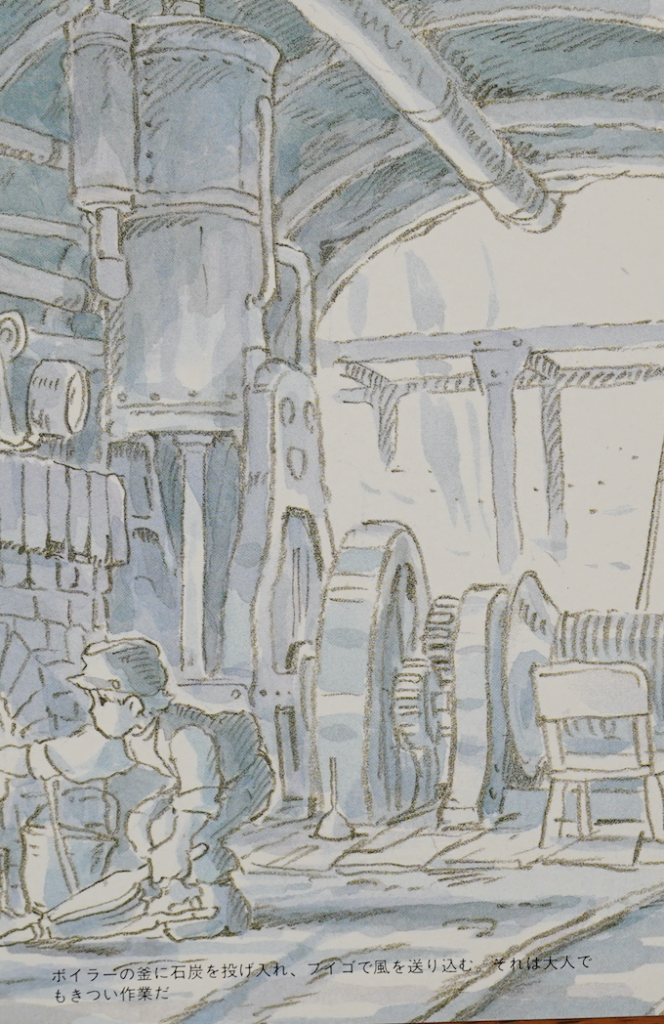

Upon arriving at the chilly morning work site, Pazu first opened the water gate. This was to fill the boiler that powered the winch for the elevator.

The equipment was old, and water dripped from the joints of the pipes.

When the water tank was full, he shoveled coal into the boiler’s furnace. Lighting it with waste oil, he pumped air using the bellows—a task so strenuous even adults struggled with it.

Soon, even in his undershirt, sweat poured from Pazu.

After confirming that the coal had ignited, he climbed up to the ceiling boards to grease the pulleys of the winch. Finishing that, he once again stoked the fire with coal, pumped in more air, and then ran to the lantern storage area.

There wasn’t a moment to think. It had taken Pazu two years to instinctively know what to do next. He polished about fifty soot-covered lanterns, filling each one with oil. They couldn’t be lit yet. They had to be handed over right before the miners came in.

Having finished these preparations, Pazu stripped off his sweat-soaked undershirt and wrung it out.

Steam rose from the cloth-like garment as droplets of sweat dripped onto the boards. Steam also emitted from his small but surprisingly muscular body.

As he wiped himself down with his undershirt, Pazu checked the boiler’s steadily increasing pressure, sighed in relief, and laid his still-warm body on the boards.

From there, he could see the remains of a stable halfway down the shaft, a relic from before the mine was mechanized. Back then, ore was loaded onto horses and transported from deep underground tunnels.

“Once a horse was lowered underground, it worked there until it died,” he recalled hearing from Pom, a living encyclopedia of the mine.

Each time Pazu remembered this story, he felt a pang in his heart. Not just for the horses, but also for the miners working there… and, of course, for himself.

As he was pulling on his cool undershirt, thinking the foreman would be arriving soon, steam burst from the boiler’s safety valve.

“Damn, that was close.”

Pazu rushed to reduce the boiler’s pressure.

“Whew… It would be bad if the foreman saw this. ‘What are you doing! Coal isn’t free, you know!'”

Imitating the foreman’s catchphrase, Pazu playfully joked to himself.

Being properly prepared was expected, and there were no praises for it. But any slight hesitation, and the foreman’s arm would come flying.

“I wonder what face the foreman will wear today.”

Even the day after having a big fight with about ten people, the foreman entered with his usual stern face. Today, Pazu didn’t want to see the foreman’s lonely expression.

Then, there was the sound of rough footsteps.

“Good morning, foreman.”

“Ah, preparations are all good, right?”

“Yeah, the boiler’s running smoothly.”

Pazu tried to read the foreman’s face, but it seemed unchanged.

Watching the foreman start his usual inspections, Pazu felt strangely relieved.

Eventually, after handing lanterns to the arriving miners, Pazu listened to the rich sound of steam from the fully pressurized winch as the foreman began its operation. It sounded even more comforting than usual.

Morning preparations wound down, but Pazu’s tasks weren’t over.

Aside from eating potatoes roasted at the boiler’s ash outlet at noon, Pazu works tirelessly – tightening the valves of the various pipes for water, steam, and gas, repairing the scaffolding planks, and of course, checking on the boiler. In the summer, salt would ooze from his body, sometimes turning him pale all over.

And unless something special happened, the “long, long day” would end at dusk.

But today was different.

As it began to get dark outside, the foreman and the engineer were discussing something loudly, their voices competing with the machine noise.

“That’s why there might be a significant vein,” one of them said.

The engineer showed the ore he held in his hand to the foreman.

“The guys below are saying to keep digging this way.”

The foreman, whether understanding or not, tapped the ore lightly and nodded.

“Alright, I’m on board. Let’s give it a shot.”

No matter how many times they faced disappointment, you never know what will happen in a mine.

The foreman, having sent the engineer back into the mine, called Pazu.

“Hey, go buy some food. I’ll watch the boiler.”

“Is it overtime? I’m on it.”

Pazu replied cheerfully.

His body was exhausted, but if there’s a “hit,” he wouldn’t mind at all. If things go well, there might even be a special bonus. Suddenly, Pazu thought of the fittings for an airplane that he couldn’t afford.

Pazu grabbed a bucket and left the mine entrance.

The rain had already stopped, and here and there, the moonlight shone through the gaps in the clouds.

Pazu, almost dancing with joy, hurried to the diner located in the mining housing alley.